A Century of Women - 1940s

Context

The 1940s was dominated by the Second World War (1939-45). Conscription was not imposed in Northern Ireland so there was little shortage of male labour; however, women still had wartime employment opportunities, particularly in linen production. While the north escaped the hardships suffered in Britain, it did experience serious air raids in 1941 and the civilian population – male and female - played an important part in war-time defence. The end of the decade witnessed the introduction of the welfare state, which began to alleviate some of the worst effects of poverty, particularly with regards to health.

The worst impact of the war in Northern Ireland occurred during April-May 1941, when a succession of German bombing raids over Belfast, Bangor and Derry left a total of 942 dead, 56,000 houses badly damaged, 100,000 people homeless and 49,000 officially evacuated. The worst-hit areas were in Belfast, where the poor state of housing became very apparent. Emma Duffin, who had worked as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse in Egypt and France during the First World War, volunteered for service and was appointed Commandant of the Voluntary Aid Detachments. Her diary described the impact of the blitz on Belfast and the appalling scenes in St George’s market, which was used as a mortuary for the dead.

Civilians played a vital part in wartime defence. The government set up a national Air Raid Precaution organisation, encouraging ordinary members of the public to volunteer. Men and women became Air Raid Wardens, members of the Auxiliary Fire Service and the Civil Defence Nursing Service, Red Cross and St. John’s Ambulance. They were allocated blocks of streets. Their tasks were to direct people into the shelters when the air raid warning sounded, making sure that no outside lights were showing and rescuing people trapped in collapsed buildings. Thirty-four wardens, both men and women, were killed in the Belfast raids. The Women’s Voluntary Services for Civil Defence enrolled and trained women to assist local authorities in the event of air raids and evacuations and with the running of canteen services, rest centres, transport and first aid. The Housewives’ section organised on street or village basis and, working under the Air Raid Precautions wardens, maintained a membership of more than 24,000. Blue Housewives’ Section cards placed in parlour windows indicated that trained women were ready to give assistance, and became a familiar sight everywhere; red cards were used to indicate a street leader.

Wartime conditions also provided increased opportunities for employment and women worked in linen manufacturing, engineering, aircraft manufacture and rope making, with a ‘modest’ rise of around 7,000 in the numbers of insured women workers. In order to facilitate women into the labour force at a time when many men had volunteered to fight in the armed forces, the Stormont administration agreed to support nurseries for working mothers. Although the Northern Ireland government was slow to support such provision, in 1941 nursery centres began to be established in rural areas such as Ballycastle, Bushmills and Lurgan, primarily for evacuated children. In 1943, further centres were established in Belfast, initially funded by the Ministry of Commerce as they were aimed at children of industrial workers. In 1942, a Nursery Centres Committee was established. By 1944, there were seven-day nurseries in Belfast and two ‘residential’ nurseries on the Saintfield and Antrim Roads where children boarded, allowing women to work night shifts, all funded by the Ministry of Education. As the expected evacuees did not materialise, the nurseries in country areas were soon used by local women. There was a large demand and the nurseries did not meet all the need, as there were long waiting lists. Nursery centres continued to operate after the end of the war but funding was withdrawn and all had closed by 1950, despite petitions and campaigns by the women using them. Four nurseries that had been set up by employers closed when the wartime linen boom ended in the mid-1950s.

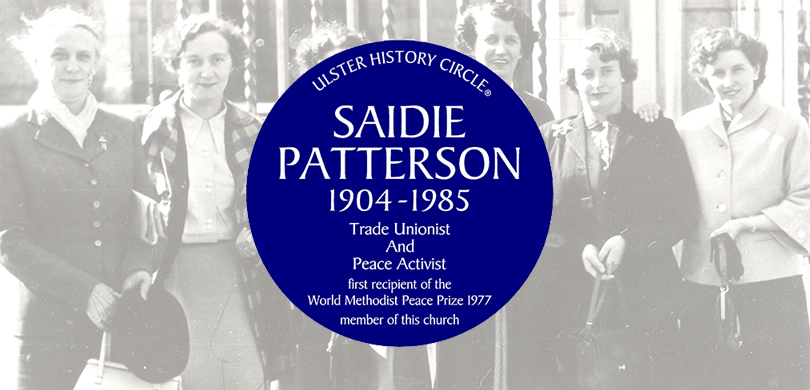

Saidie Patterson, a weaver at William Ewart’s mill, took the opportunity afforded by the war conditions, and the consequent demand for linen, to lead a seven-week strike as part of a campaign by the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers’ Union for a closed shop in the linen industry. In a speech she gave during the strike, Patterson explained that there were no trade boards or any other mechanism, to regulate wages in the industry, which is why they wanted ‘a strong 100% trade union organisation, capable of demanding better conditions for the thousands of textile workers, instead of merely pleading for them.’ The strike was unsuccessful, but Patterson believed that they had contributed to the battle for better conditions.

As conscription was not imposed upon Northern Ireland, rural areas experienced less shortage of male labour than in Britain. Many politicians objected to the setting up of a Northern Ireland Women’s Land Army on grounds that women were incapable of heavy labour and there was a danger that it would only serve to exacerbate rural unemployment, which was already at high levels. However, there was a great need for increased cultivation of land, given the difficulties of importing food and the compulsory Tillage Order of 1939, which stipulated that every farmer had to plough an additional one-tenth of arable land. As a result, the demand for female labour increased. However, after 1945, as farmers moved away from tillage to the more profitable areas of pasturage and dairy farming, the numbers of female agricultural workers rapidly declined to pre-war levels and the post-war years saw rural women return to the traditional domestic arena.

Male policing of women and fears about women’s morality were common concerns in Britain and Ireland during both the first and second world wars. Increased employment opportunities, the presence of young men from the armed forces on the streets, and the growing independence of many young women during the war years led to concerns being voiced by politicians and by churches. Women’s patrols had been established in Belfast and Dublin during the 1914-18 war to protect young women from the attention of the increased number of soldiers, and these reappeared on the streets of Belfast. In addition, a conference in Belfast in 1942, attended by representatives of the Council of Social Welfare and the Church of Ireland Moral Welfare League, met the Minister of Home Affairs and the head of the RUC to discuss the need for female police officers to look after the welfare of women and young girls. There were increased prosecutions for prostitution and brothel keeping during the war years, reflecting the presence of large numbers of foreign troops based in Northern Ireland.

Betty Sinclair, a trade unionist, and member of the Belfast District of the Communist Party of Ireland, was extremely active in urging women to support the fight against fascism, conscious of the burden of war, that the Soviet Union, an ally of Britain, was experiencing. Her pamphlet on Women and the War urged women of Northern Ireland to be ‘as capable and heroic as the women of the Soviet Union’, so that a Second Front could be opened up in Europe, enabling ‘the utter destruction of Hitlerism and all brands of fascism.’ Sinclair, on behalf of the Communist Party, also took the opportunity afforded by the Belfast Blitz and the loss of houses to issue a pamphlet to campaign for more money to be spent on public housing and slum clearances. This was entitled Homes for Ulster: an explanation of the Communist Party’s Policy for Northern Ireland (1944); the pamphlet was a response to an Interim Report of the Planning Advisory Board on Housing.

While there was little evidence of women’s activism in the post-war period, other than philanthropic work within church-based groups, the Standing Conference of Women’s Organisations for Northern Ireland was established in 1943, with Saidie Patterson playing a leading role. Lilian Calvert acted as a chair of this organisation from 1945-47. Calvert, who had worked as a wartime Chief Welfare Officer, went into politics because she wanted to introduce progressive social legislation. She had a degree in economics from Queen’s University and hoped to be able to ‘put the women’s point of view’ across. However, in 1953 Calvert resigned from Stormont, declaring that the Northern Ireland statelet was not a viable economic unit.

The post-war period saw a number of positive changes, emanating from Britain, which the Stormont administration reluctantly implemented, creating the modern welfare state with a National Health Service, an education act that raised the school leaving age and improved educational facilities and a programme of house building, although allocation of housing was marred by discrimination against the Catholic minority population. However, with the closing of nurseries and the loss of wartime employment opportunities, women, in general, found that they were entering a conservative period, which emphasised the importance of their work in the home.

In terms of culture, this period saw the formation of the Ulster Group Theatre, which gave a number of women the opportunity to develop careers in the theatre. Nita Hardie, a founding member, was also a producer, director and actress. Beatrice Duffell was also a founder and Elizabeth Begley was described as a ‘leading lady of Northern Ireland theatre.’ Anna McClure Warnock wrote and performed in radio dramas.

Timeline

1940

- Ulster Group Theatre is established in March.

- Northern Ireland Women’s Land Army established.

- Saidie Patterson leads a 7-week strike at Ewart’s linen mill.

- Betty Sinclair is imprisoned for two months in Armagh Jail for publishing an article written by Sinn Fein in the Communist Party of Ireland’s Northern paper, The Red Hand.

1941

- Nursery centres are established in country areas.

1942

- Nursery Centres Committee is established.

- Betty Sinclair urges women in Northern Ireland to support the fight against fascism.

- 1943

- Nurseries are set up in Belfast.

- Women’s Volunteer Patrol is set up in September.

- Standing Conference of Women’s Organisations in Northern Ireland is established.

- Six policewomen are appointed in November following a conference in 1942.

- Winifred Carney dies.

1945

- At the general election on 14 June to Northern Ireland parliament, three women are elected: Lilian Calvert (Independent); Dehra Parker (formerly Chichester), Unionist; Dinah McNabb, (Unionist).

1947

- Betty Sinclair becomes full-time secretary of Belfast and District Trades Council.

- Butler Education Act is introduced in Northern Ireland amid controversy and opposition from both Unionists and the Catholic Church. The leaving age for compulsory schooling is raised to 15, with a system of secondary grammar and intermediate schooling introduced at the age of 11. Facilities such as milk and dinners are made available. Grants are introduced for University education.

1948

- The NHS is rolled out in Northern Ireland, introducing free consultations with doctors, dental and eye practitioners, free prescriptions and a reorganisation of hospitals. Family allowances, unemployment benefit, national assistance and maternity benefits improve the quality of life for the poorest groups.

1949

- 10 February general election, four women are elected: Lilian Calvert, Dehra Parker, Dinah McNabb and Dr Eileen Hickey (Independent, QUB).

1950

- All wartime nurseries are closed.

Reading

Myrtle Hill, Women in Ireland: a century of change (Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 2003).

Gillian McIntosh, ‘’Who’s looking after baby? Nursery school care in Northern Ireland During the Second World War’, in Gillian McIntosh and Diane Urquhart (eds) Irish Women at War (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2010).

Clare O’Kane, ‘“To Make Good Butter and to look after poultry”: the impact of the Second World war on the Lives of Rural Women in Northern Ireland’, in Gillian McIntosh and Diane Urquhart (eds) Irish Women at War (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2010).

Leanne McCormick, “Filthy Little Girls”: Controlling Women in Public Spaces in Northern Ireland during the Second World War’, in Gillian McIntosh and Diane Urquhart (eds) Irish Women at War (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2010).

Speeches and writings from Saidie Patterson and Betty Sinclair and diary extract from Emma Duffin in The Field Day Anthology of Women’s Writing, Vol. V (Cork: Cork University Press, 2002).

Maedhbh McNamara and Paschal Mooney, Women in Parliament Ireland: 1918-2000 (Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 2000).

David Bleakley, Sadie Patterson: Irish Peacemaker (Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 1980)

Hazel Morrissey, ‘Oral History: Betty Sinclair: A Woman’s Fight for Socialism, 1910-1981’, Saothair na hEireann Journal of the Irish Labour History Society (1983), pp. 121-32.

Lily Anderson, Portrait of a Communist Woman (National Women’s Committee, Communist Party of Ireland, 1982)